By Hari Basnet, Research Associate, Class of 2023

I still remember rushing back to my apartment in Kathmandu after receiving the Barun Valley camera trap data. The excitement of checking those photos never fades. I skimmed quickly to see if we have any exciting animals. When I was skimming Kali Khola station photos, I slowed down. This camera trap station is a natural funnel: a cold, fast stream pushes animals under a rock overhang and through a narrow corridor. Most photos showed the usual visitors, large herbivores such as Himalayan Goral with young; Mainland Serow licking minerals at night; a Barking Deer stepping cautiously in daylight or Blue Whistling Thrush exploring the dump area for food. Then suddenly, one frame stopped me cold. A glowing eye pierced the darkness, reclining posture with a tail structure that was very long and marked with distinct black and white bands. My heart leapt. On 6 November 2019, at 02:30 a.m., the Spotted Linsang passed through our camera trap and we got evidence of one of the most elusive nocturnal carnivores in Southeast Asia.

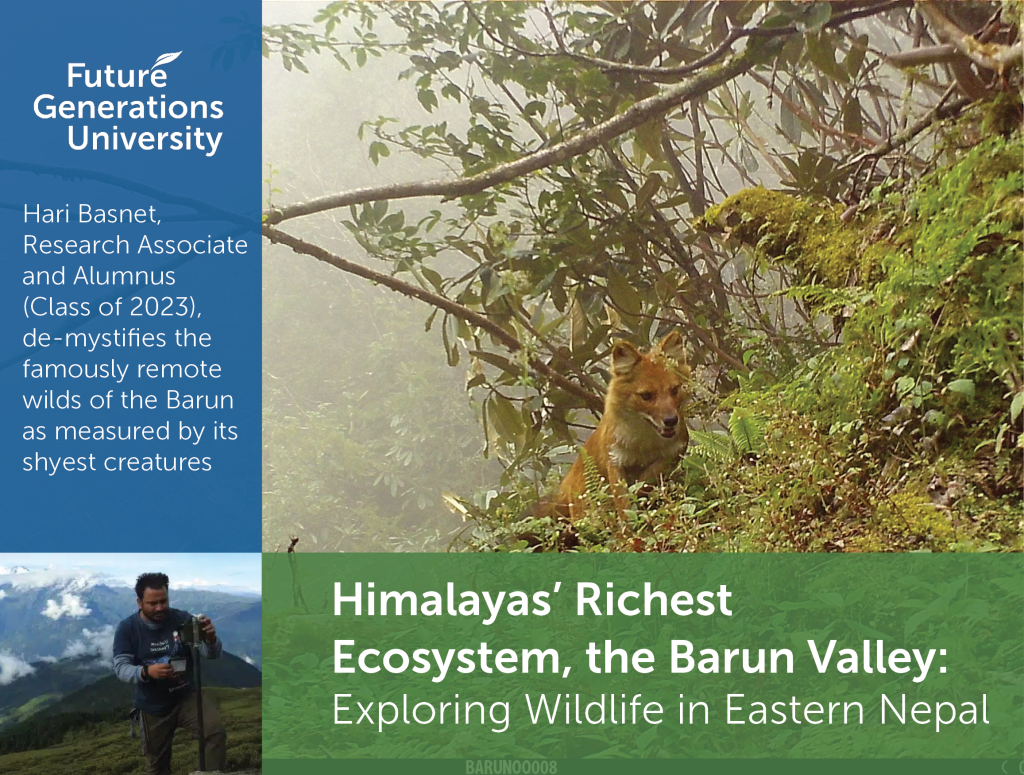

Two years later, in summer 2021, I was checking through hundreds of false-trigger images from Bagare, a camera set in a natural bottleneck at ~3,000 m where the Barun River presses one side and a sheer cliff the other. Then one frame stopped me: in bright daylight a Dhole was running across the mossy slope, with its bushy black tail held straight behind its body (picture below, on the right). Fatigue vanished and my heart raced, after years of herders’ fading stories, this was undeniable proof that the Asiatic wild dog still roamed Makalu Barun.

From Myth to Protection

The story of Barun’s protection begins with curiosity and, yes, a legend. Daniel C. Taylor first walked into the Barun in the 1970s chasing the Yeti’s tale. He later told me, “What began as a search for a mythical creature turned into protecting a living landscape.” His observations, and those of Nepalese botanists like Dr. Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha, who called the valley “Nepal’s last pure ecological seed,” helped persuade authorities and communities that Barun was worth saving. Even His Majesty King Birendra shared the concern that, without action, the Barun Valley would eventually be settled with villages.

Makalu-Barun National Park was established in 1992 and a surrounding buffer zone created to support both conservation and local livelihoods. Our camera records now offer modern proof that protection can work: that legal safeguarding and local stewardship together allow wild systems to persist.

Barun Valley is a study in extremes. The park rises from roughly 435 meters to Mt. Makalu’s summit at 8,463 meters, compressing subtropical, temperate, alpine and nival zones into a relatively narrow band. This steep elevation gradient creates microhabitats stacked like shelves, and many animals move along narrow corridors where those shelves meet.

Half a century after Barun first captured global attention, the Barun Biomeridian Project began with a new goal: to gather evidence that can help local communities adapt to climate change while protecting their valley’s biodiversity. Using modern technologies, the project combines three ways of knowing nature: climate sensors that feel shifting conditions, camera traps that look at elusive wildlife, and bioacoustic recorders that listen to the valley’s soundscape. Together, they create a living library of Barun’s ecological pulse across the Himalaya.

We placed nine camera traps along a 40-km transect (= Yeti Trail) spanning across elevation gradients from 2000-3800 m. The idea was simple: put the camera traps where animals must pass. Even a small network can reveal a great deal. Over 6,896 camera traps nights (2019–2024) we reviewed roughly 9,575 photographs and recorded 28 mammal species (not counting small mammals and many bats, which are harder to identify from camera trap images). Among them were eight globally threatened species and four species photographed in the park for the first time.

The Linsang at Four Different Stations

Since the first recording was transmitted, we have recorded 12 independent events across four stations (records are counted as an independent event if the same species doesn’t appear again for at least 30–60 minutes in front of the same camera), in what could be one of the highest numbers of independent events recorded for this species in the world. Linsangs are listed as Endangered on the National Red List of Nepal and also one of the 27th protected priority species; these multiple detections across different stations are significant. They hint that the linsang is more adaptable in elevation than previously thought and that Barun’s abundant oak rhododendron forests with dense undergrowth vegetation provides a critical refuge.

Each nocturnal image felt like a rare glimpse, a reminder that camera traps can capture mysteries that field observation alone could never reveal, mysteries invisible even to pioneers like Daniel Taylor and Dr. Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha when they first explored the Barun on foot.

The Dhole at Bagare and Bharyang Khola

The Dhole’s photograph felt different—less mysterious, more immediate. Normally, these wild dogs are social, hunting in coordinated packs, yet every one of our six records from two stations showed a solitary individual. Its presence confirmed what some elders had whispered: dholes still move through these valleys. But why alone? Are populations too small for stable packs, or are they dispersing from neighboring landscapes like Kanchenjunga? Could the Barun Valley be the place where they begin to form packs again? The Barun offers everything they need—steep terrain, dense forests, and abundant prey such as Himalayan tahr, goral, and macaques. Globally listed as Endangered, dholes are a keystone predator, and their disappearance would ripple through the entire ecosystem.

Ecological Significance of the Findings

While not every camera trap record carries equal weight, these observations highlight Barun’s ecological importance. The Spotted Linsang was recorded in 12 events across four stations, underscoring Barun as a core refuge for this elusive species. The Dhole’s presence demonstrates that top predators, although rare, continue to traverse these valleys, playing a crucial role in maintaining the structure and stability of the food web. Clouded Leopards were detected in notable numbers, while Himalayan Black Bears, Himalayan Serow, Himalayan Ghoral, martens, and macaques were observed at more than seven of nine stations, reflecting the widespread and active use of habitat by mid- and large-sized mammals.

Moreover, records of threatened species, including the Himalayan Musk Deer and Himalayan Red Panda across three stations, alongside small carnivores such as three mustelid species and four cat species—including Leopard, Asian Golden Cat, and Leopard Cat—illustrate that Barun is far from a degraded landscape. Instead, it functions as a vibrant, interconnected ecosystem, supporting multiple trophic levels and a remarkable diversity of Himalayan wildlife. These findings position Barun as a living repository of biodiversity and a key area for conservation action.

People on the Ground

Syaksila Village is the last village before the Barun Valley. Dukpa Thikepa, a local assistant who conducts fieldwork every three months, put it simply: “Living in Syaksila village, I have never thought of having such diversity of mammals that we captured in camera traps and some of these are never seen by the locals.”

He is a local leader who knows how and where you put camera traps and how to manage an expedition. When we projected the wildlife of Barun including Linsang and Dhole photos in the community meetings, people were super excited to see this wildlife. So, reaction matters: conservation succeeds where communities see value in protecting their land. The cameras do more than document species, they provide shared evidence that can unite villagers and park managers around practical actions.

Challenges and Next Steps

Working in the Barun Valley is as much about endurance as it is about science. Just getting there is a journey in itself. From Kathmandu, it takes either a 15-hour drive to Khadbari or a short flight to Tumlingtar, followed by a punishing 7–8 hour off-road jeep ride and then several days of trekking through rugged wilderness. Beyond Syaksila village, there are no tea houses or permanent shelters until you rejoin the Makalu Basecamp route at Jate. We relied entirely on tents or, when the weather turned, tucked ourselves under dripping cliffs and rock overhangs. The trails are narrow and steep, often clinging to the side of the valley wall, and there is no phone signal or radio network. Every step had to be deliberate, one misstep on the wet rocks could have meant serious injury, far from help.

The valley itself never lets you forget how wild it is. I still remember the unease of walking through dense bamboo, knowing that Himalayan black bears, and sometimes even brown bears, were moving through the same forest. Our cameras confirmed what we felt in those moments: bears were often there in daylight, watching the same trails we used. And then there were the limits of our resources. We had only nine camera traps for the whole valley, with just three positioned above 3,000 meters, the very alpine zones where many threatened species are found. Snow regularly blocked access or buried the cameras, and on some trips we found units damaged or tampered with. I often wondered what more we might discover if we had even a dozen more cameras scattered along the valley’s ridges and rivers.

The findings highlight the need for continued monitoring, particularly of species such as the Dhole. Key questions remain: will Dholes establish a permanent presence in the valley, and if so, how might their return influence ecosystem dynamics as a top predator? Current monitoring is limited, with only two stations in the alpine zone. Expanding the network of camera traps and survey sites would provide more comprehensive data on species distributions and ecological interactions.

Resource constraints over the past five years have restricted the scope of research, limiting opportunities for upgrading equipment and expanding surveys. Yet, gathering additional data is essential to reveal ecological patterns, understand the role of keystone species, and assess the effects of top predators on ecosystem functioning. Beyond scientific insights, these data can inform local communities, raising awareness about the wildlife around them and promoting the conservation of Barun as a largely intact, functioning ecosystem from which people can benefit.

A Valley of Secrets and a Call to Action

I close my eyes and the Barun comes alive. Clouded Leopards weave silently through the shadows, tails curling like question marks. Golden cats, each with its own pattern, follow in quiet curiosity. Black Bears pause, sniffing the air or rubbing against ancient trees, while Dholes ghost across the alpine valleys, their presence felt more than seen. In these moments, Barun’s heart beats wild, untamed, alive.

This is no mere place of stories or myths. Barun is a living sanctuary, fragile yet fierce, where every creature plays its part in a delicate balance. Protecting it is more than conserving wildlife, it is keeping one of the Himalaya’s last true wild frontiers intact. So that someday, someone else might feel the same awe, the same thrill, when a hidden creature steps quietly into view.

Resource constraints over the past five years have restricted the scope of research, limiting opportunities for upgrading equipment and expanding surveys. Yet, gathering additional data is essential to reveal ecological patterns, understand the role of keystone species, and assess the effects of top predators on ecosystem functioning. Beyond scientific insights, these data can inform local communities, raising awareness about the wildlife around them and promoting the conservation of Barun as a largely intact, functioning ecosystem from which people can benefit.

HARI BASNET

Research Associate

hbasnet@future.edu

Education

– Master of Arts in Applied Community Development, Future Generation University, USA, 2023

– Master in Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Central Department of Zoology, Nepal, 2015

About Hari Basnet

- IUCN Species Survival Commission– Galliformes Specialist Group, Since March 2017 to present

- Life Member, Small Mammals Conservation and Research Foundation, Bird conservation Nepal and Pokhara Bird Society

- Technical team member:

- Pheasant Conservation Action Plan for Nepal (2019-2023),

- Checklists of Fauna of the Seti River Corridor,

- Site specific Conservation Action plan for bats in the Kathmandu valley, Nepal, Reviewer: Pangolin Monitoring Guidelines for Nepal, 2019 and Supervised two master’s thesis from Tribhuvan University