A Shared Landscape of Challenge—and Possibility

From the hills of Phalombe region and neighboring districts in southern Malawi to the urban and peri-urban corridors of Khartoum and River Nile states in Sudan, communities face intertwined forces that deepen poverty and vulnerability:

- Climate shocks: floods, droughts, and soil degradation that disrupt crops, housing, and health.

- Displacement and migration: families uprooted by civil war or climate impacts, forced to rebuild with little.

- Strained infrastructure and unequal access: water systems, health facilities, and markets that are too distant, damaged, or under-resourced.

- Economic challenges: limited credit and employment opportunities—especially for youth and women—restrict the pathway out of poverty.

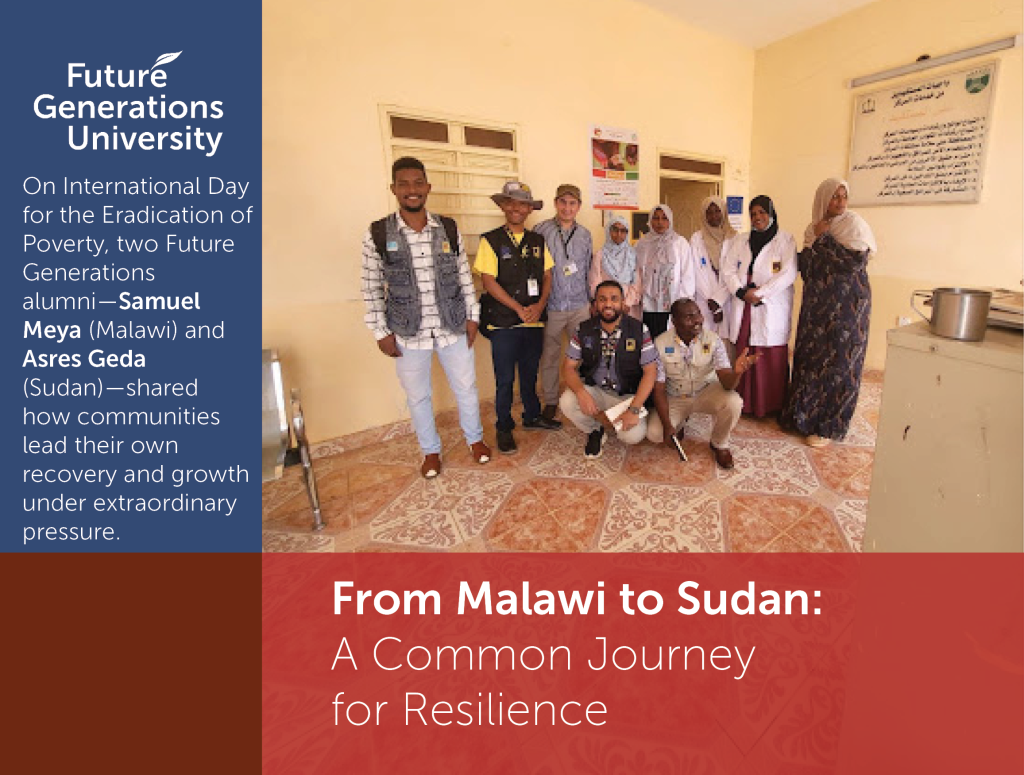

Against this backdrop, alumni-led action shows how participation, evidence, and local leadership can convert immediate relief into lasting resilience. The following are condensed highlights from the October 17 Success Sharing Session.

Malawi — Samuel Meya: WASH, Behavior Change, and Economic Empowerment

Samuel Meya, Executive Director of Goodwill Community Development Partners, has worked across the region—including South Sudan—before returning to Malawi to deepen community-led WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene). His starting point is simple and radical: ownership.

“WASH implementation is holistic. It needs a holistic approach. And mostly, in WASH, we use a number of participatory approaches so that we may consider people’s participation and involvement.”

Participatory approaches that build agency

Samuel’s team blends SEED-SCALE principles with tools such as Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST), Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA), community-based management, and Asset-Based Community-Driven Development (ABCDD).

“All these, we use so that we mobilize our subjects… mostly to instill a sense of ownership in our communities, because WASH is very expensive, and for it to be sustainable, people need to take responsibility for whatever investment we are making in them.”

Ownership is practical, not rhetorical: communities contribute sand, bricks, and labor, elect local leadership committees, and establish maintenance funds—now formalized through community bank accounts—to keep systems working long after projects end.

The sanitation ladder: from a first latrine to lasting dignity

Samuel emphasizes the sanitation ladder—supporting households to move from open defecation or temporary pits to safer, more durable facilities, sometimes up to flush-standard where feasible.

“We encourage people to have at least a latrine… and then we use participatory approaches to help them improve step by step.”

Local masons trained from within the community—coach neighbors to build low-cost, low-timber designs using local materials. Some innovations include cement-free options and pre-cast slabs that improve safety and can even integrate with biogas systems.

Behavior change: making the invisible visible

Infrastructure alone doesn’t stop disease. Samuel’s teams lead mass communication, panel discussions, and school-based hygiene education, with simple demonstrations that make microbes “real”:

“We promote handwashing with soap because soap cleans hands thoroughly… Using egg and cassava tests, we show that when people just wash without soap, the dirt remains.”

Crisis at scale—and the courage of local staff

Asres frames the crisis starkly:

“Sudan is facing the world’s largest humanitarian crisis… almost 30 million people are in need, and around 12 million have been displaced.”

The numbers are numbing, but the human story is bracing:

“Almost 90% of our staff become IDPs themselves… They shifted from one place to another, but at the same time, they were able to support the internally displaced people.”

This community resilience in crisis is the beating heart of Sudan’s response—host families and local professionals stepping forward even as they, too, are displaced.

From maintenance funds to livelihoods: Village Savings & Loans

Perhaps the most striking lesson is how WASH finance morphed into Village Savings & Loan (VSL) groups. After setting aside money for spare parts, communities have pivoted their behavior to now lend to each other to start small enterprises—turning a repair fund into a poverty-reduction engine.

“People started in a small way to use the maintenance fund as part of savings and loans… This has scaled up.”

The outcomes are measurable and powerful:

“The repayment rate is 99.8%, and the default rate only 0.2%. This shows ownership—people are enjoying the fruits of their sweat.”

Households invest in better latrines, small businesses, and home improvements, and some communities expand sanitation marketing—artisans casting slabs, promoting safer designs, and creating local demand.

Climate-smart sanitation

Samuel’s WASH work also intersects with climate resilience. Communities experiment with composting fecal matter and urine diversion to produce nutrient inputs (“the feces as compost, the urine like urea”), integrate biogas to reduce cutting of trees, lowering input costs while restoring soils and protecting forests.

The through-line is unmistakable: participation begets ownership; ownership sustains systems; sustained systems unlock livelihoods.

Sudan — Asres Geda: Restoring Systems Amid Crisis

Asres Geda, Senior Field Coordinator with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) Sudan Country Program, leads large, multi-sector teams across River Nile and Khartoum—the latter was an epicenter of Sudan’s war but now is getting stable. His account brings into focus the scale and complexity of crisis response.

“I am leading two big field offices… Our response is integrated: health and nutrition, WASH, protection, and cash assistance.”

Protection, dignity, and cash assistance

Beyond clinical and WASH interventions, Asres’s teams run integrated protection—women’s and girls’ dignity kits, GBV risk assessments, case management, income generating life skills, and psychosocial support—and multi-purpose cash assistance so families can cover food, medicine, rent, and essential goods.

“Cash assistance is life-saving… We engage communities to identify the most vulnerable and set the transfer size based on market assessments.”

Pressures on infrastructure—and a call for sustained support

Asres is candid about constraints: damaged power and water systems, access barriers in active conflict zones, and the pressure on host communities as IDPs strain already-fragile services.

Yet amid the turmoil, there are signals of recovery:

“We’re able to manage 5 primary healthcare centers and 3 nutrition facilities in River Nile, and 7 primary healthcare centers and 4 nutrition facilities in Khartoum… reaching around 150,000 beneficiaries—on pace for half a million by year’s end.”

His closing message is both a report and a plea:

“Sudan is facing the world’s largest humanitarian crisis… more support is needed to restore basic services and enable people to return and rebuild their lives.”

Shared Lessons: Community Strength as the Engine of Recovery

Placed side by side, Samuel’s and Asres’s experiences illuminate a common pathway from survival to stability—and, crucially, to self-directed growth.

- Participation → Ownership → Sustainability

- In Malawi, households co-invest, manage maintenance funds, and grow VSLs that finance livelihoods.

- In Sudan, local professionals staff clinics; host families absorb displaced neighbors; volunteers drive hygiene and protection outreach.

SEED-SCALE is visible in practice: build from what works, widen the circle, and let evidence guide next steps.

- Health systems and WASH are inseparable

- A clinic without water is a building; a tap without hygiene is a missed opportunity.

- Institutional WASH in Sudan and community WASH in Malawi both show that behavior change is as critical as hardware.

- Crisis can catalyze social infrastructure

- Maintenance funds become community banks; host families become safety nets; trained masons become sanitation entrepreneurs.

- When the “how” belongs to the community, scaling is multiplication, not replication.

- Climate resilience is local and practical

- Composting and biogas link sanitation to soil fertility and energy savings.

- Flood, cholera, and drought response hinge on prepared facilities, trained people, and adaptive norms.

Closing Reflection

Future Generations University teaches that people are not problems to be fixed; they are the solution to be supported. On a day devoted to ending poverty, Samuel and Asres remind us that progress is not a single program or project—it’s a way of working that respects human energy, shares responsibility, and grows from success.

Samuel’s words linger as an invitation:

“We build from what people already have. That is where the power lies.”

And Asres adds the call we must not ignore:

“Sudan is facing the world’s largest humanitarian crisis… more support is needed so people can return and rebuild their lives.”

Across Malawi and Sudan, the path forward is the same: enable communities to lead, strengthen systems that dignify life, and widen the networks that carry resilience from one village, one clinic, one family—to the next.