2023:

The Year King Kong Body Slammed the West Virginia Maple Syrup Industry

By Mike Rechlin and Bob Leffler

February is when we make maple syrup in West Virginia. A good season takes us into March, and we can (and probably should) start tapping in January. But February is when conditions are prime for sap flow. So, this year we did just like we always do: checked our lines, changed our spouts, charged up our drills, and tapped our trees in February. Most West Virginia producers could have tapped earlier, but late January saw high temperatures that hit 70 degrees, and it just didn’t feel right to be in the woods tapping when the weather was that warm. Instead, we waited for winter to arrive, and it eventually did.

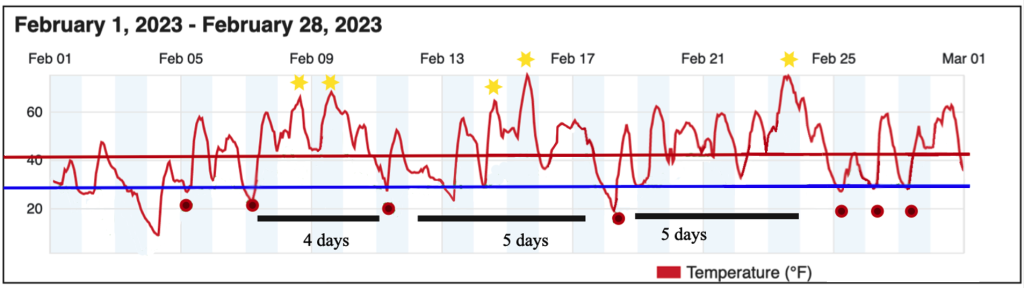

The first few days of February were cold, and tapping drills were a’ hummin’ and sap was a’ flowin.’ But then things went south. The next three weeks saw five days in Franklin, West Virginia, where daily high temperatures were 65 degrees or higher. What was even worse, we had three extended thaws where the nighttime temperatures only dipped to the low 30s at best (figure1). By February 21, many West Virginia producers were packing it in, some pulling taps before they had collected enough sap to even fire up their evaporators.

What happened?

Did climate change catch up with us and relegate the Appalachian maple syrup industry to the trash bin of history, along with whaling industry of New England or the mussel harvesting industry (the shells used to make buttons before the arrival of plastic) of the Midwest? Well, the answer is no, or at least not yet. But climatic conditions and a weather anomaly were indeed responsible for a season in which most producers had well below their average yield.

What happened?

Did climate change catch up with us and relegate the Appalachian maple syrup industry to the trash bin of history, along with whaling industry of New England or the mussel harvesting industry (the shells used to make buttons before the arrival of plastic) of the Midwest? Well, the answer is no, or at least not yet. But climatic conditions and a weather anomaly were indeed responsible for a season in which most producers had well below their average yield.

In West Virginia, climate is very much related to elevation. For every thousand-foot change in elevation, the average temperature decreases by about 3.3 degrees Fahrenheit. Potomac Highlands producers, with sugarbushes located at between 3,500-4,500 feet, look a lot closer ecologically and climatically to our northern neighbors than they do to the community 20 miles, and 2,000 feet lower, down the road. This year the magic elevation seemed to be about 3,000 feet. Producers above that elevation were alright. Producers below that were “screwed” or maybe more appropriately for this article “body slammed.” And that’s where King Kong comes in.

Figure 1. February 2023 temperatures from Weatherunderground station KWVFRANK12.

King Kong

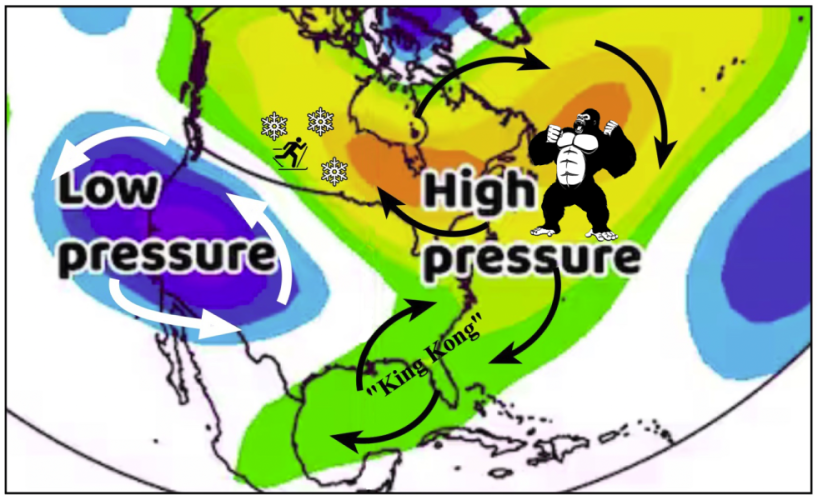

King Kong is the nickname given by “The Fearless Canaan Valley Weatherman” Bob Leffler to a high- pressure ridge that ran diagonally from the coast from Bermuda through to the Gulf of Mexico (figure 2). Bob is a retired National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologist/climatologist who issues complimentary winter weather forecasts for the WV Canaan High Country during the colder half of the year.

Weather systems normally move from west to east across the country. This weather anomaly, called a blocking ridge, or wall, developed in January and stayed put until the end of February. It produced a strong southwest air flow aloft and at the surface, which blocked more typical intrusions of colder Arctic air from penetrating into West Virginia and resulted in the very mild temperatures over much of eastern North America in January and February.

King Kong is the nickname given by “The Fearless Canaan Valley Weatherman” Bob Leffler to a high- pressure ridge that ran diagonally from the coast from Bermuda through to the Gulf of Mexico (figure 2). Bob is a retired National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologist/climatologist who issues complimentary winter weather forecasts for the WV Canaan High Country during the colder half of the year.

Weather systems normally move from west to east across the country. This weather anomaly, called a blocking ridge, or wall, developed in January and stayed put until the end of February. It produced a strong southwest air flow aloft and at the surface, which blocked more typical intrusions of colder Arctic air from penetrating into West Virginia and resulted in the very mild temperatures over much of eastern North America in January and February.

Figure 2. The high-pressure blocking ridge known as King Kong.

The effects of this blocking high pressure wall were quite local. Geauga County Ohio, near Cleveland, had an excellent sap flow season, whereas in Mansfield Ohio, just 80 miles south, the season was well below average. Areas subject to long freeze-ups in the bush had milder conditions with more freeze- thaw cycles and a good syrup crop. Areas where the sap flow problem was more often related to taphole drying due to extended warm spells did not.

But where did King Kong come from, and most importantly, will we see him again? Enter La Niña.

La Niña

The 2023 West Virginia sap flow season was plagued by two occurrences: one climatic, related to long term weather trends, and the other a weather anomaly, a chance occurrence that we may or may not see again anytime soon.

The climatic issue was La Niña, which is the cold phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). La Niña refers to the periodic cooling of ocean surface temperatures in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific. Typically, La Niña events occur every three to five years, but on occasion, it can occur over successive years. We have just seen our third consecutive La Niña tying the all-time record for continuous occurrences. The cold equatorial Pacific Ocean surface temperatures cause a shift in the global jet stream, which typically results in warmer and drier conditions in the southeast.

In terms of maple syrup production West Virginia is in the Southeast, and La Niña often leads to poor sap and syrup production, except at elevations above 3,000 feet. For most of our West Virginia producers the three consecutive La Niña years meant three years of warmer than average winters, resulting in three years of poor sap yields.

With the underlaying conditions caused by La Niña, King Kong ruled eastern North America’s roost. As shown by the black arrows on figure 2, air flows in a clockwise pattern around high-pressure systems, bringing warm air from the Gulf of Mexico to West Virginia. West of the high-pressure system was a low-pressure system. Air flows in a counterclockwise pattern around a low. We rely on cold Canadian air during the sap flow season; however, King Kong was so big and powerful that he deflected the more typical cold air masses out of Canada from reaching West Virginia during much of January and February.

The exception was that first week of February, when most of our producers tapped out, and the last week of February when King Kong took a nap and the cold air spilled in. We had only four good sap flow initiating cycles through February 24. In the next two weeks, from late February into March, and we saw nine. This year the time to make maple syrup in West Virginia was March, but for most of our producers by then it was too late.

Looking ahead

As the renown philosopher (and former NY Yankees catcher) Yogi Berra once said, “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” With three La Niña years under our belt, climate scientists expect the ENSO cycle to return to neutral or move into the El Niño phase. El Niño, the opposite of La Niña, with its warmer than average equatorial Pacific Sea surface temperatures, shift the jet stream and typically results in a colder winter.

The National Weather Service forecasts an 80 to 90 percent probability that El Niño will form by fall. El Niño is expected to bring colder and wetter conditions to parts of West Virginia for the 2024 sap flow season, but the impacts can vary from year-to-year and with elevation, so producers will have to wait and see how it plays out.

Beyond that, some scientists speculate that climate change will bring a more erratic jet stream as well as stronger El Niño/La Niña periods. What does that mean for maple syrup producers? As we are seeing worldwide, weather patterns are becoming more extreme, upending historical norms, and threatening existing economic practices. Our challenge will be to adapt our sap and syrup production practices to meet the changing weather and climate.

What role, if any, the ongoing rapidly warming climate will play in feeding King Kong in the future is the joker in the deck. In the meantime, we’ll just have to keep an eye out for that big hairy guy in the sky!

But where did King Kong come from, and most importantly, will we see him again? Enter La Niña.

La Niña

The 2023 West Virginia sap flow season was plagued by two occurrences: one climatic, related to long term weather trends, and the other a weather anomaly, a chance occurrence that we may or may not see again anytime soon.

The climatic issue was La Niña, which is the cold phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). La Niña refers to the periodic cooling of ocean surface temperatures in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific. Typically, La Niña events occur every three to five years, but on occasion, it can occur over successive years. We have just seen our third consecutive La Niña tying the all-time record for continuous occurrences. The cold equatorial Pacific Ocean surface temperatures cause a shift in the global jet stream, which typically results in warmer and drier conditions in the southeast.

In terms of maple syrup production West Virginia is in the Southeast, and La Niña often leads to poor sap and syrup production, except at elevations above 3,000 feet. For most of our West Virginia producers the three consecutive La Niña years meant three years of warmer than average winters, resulting in three years of poor sap yields.

With the underlaying conditions caused by La Niña, King Kong ruled eastern North America’s roost. As shown by the black arrows on figure 2, air flows in a clockwise pattern around high-pressure systems, bringing warm air from the Gulf of Mexico to West Virginia. West of the high-pressure system was a low-pressure system. Air flows in a counterclockwise pattern around a low. We rely on cold Canadian air during the sap flow season; however, King Kong was so big and powerful that he deflected the more typical cold air masses out of Canada from reaching West Virginia during much of January and February.

The exception was that first week of February, when most of our producers tapped out, and the last week of February when King Kong took a nap and the cold air spilled in. We had only four good sap flow initiating cycles through February 24. In the next two weeks, from late February into March, and we saw nine. This year the time to make maple syrup in West Virginia was March, but for most of our producers by then it was too late.

Looking ahead

As the renown philosopher (and former NY Yankees catcher) Yogi Berra once said, “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” With three La Niña years under our belt, climate scientists expect the ENSO cycle to return to neutral or move into the El Niño phase. El Niño, the opposite of La Niña, with its warmer than average equatorial Pacific Sea surface temperatures, shift the jet stream and typically results in a colder winter.

The National Weather Service forecasts an 80 to 90 percent probability that El Niño will form by fall. El Niño is expected to bring colder and wetter conditions to parts of West Virginia for the 2024 sap flow season, but the impacts can vary from year-to-year and with elevation, so producers will have to wait and see how it plays out.

Beyond that, some scientists speculate that climate change will bring a more erratic jet stream as well as stronger El Niño/La Niña periods. What does that mean for maple syrup producers? As we are seeing worldwide, weather patterns are becoming more extreme, upending historical norms, and threatening existing economic practices. Our challenge will be to adapt our sap and syrup production practices to meet the changing weather and climate.

What role, if any, the ongoing rapidly warming climate will play in feeding King Kong in the future is the joker in the deck. In the meantime, we’ll just have to keep an eye out for that big hairy guy in the sky!

(Visited 400 times, 1 visits today)