This summer, Seosamh interned with Future Generations University (FGU), trading the city’s concrete for the rich, forested landscapes of West Virginia. His goal was to immerse himself in the world of maple syrup and other innovative maple products, learning directly from local producers.

A Foundation in Forest Genetics

Seosamh’s journey into the sugarbush is deeply rooted in his academic research. His master’s thesis focuses on the genetic diversity in sugar maples (Acer saccharum) and he is interested in learning more about how this relates to their resilience to the pressures of climate change. He believes that by understanding the present status and health trends of key species, we can develop proactive strategies to prevent dramatic forest and biodiversity loss in eastern forests.

To investigate this, Seosamh began a project in the winter of 2023/24 with Dr. Hanna Makowski at the Carnaval Lab. Their research examines the relationship between leaf phenology—the life cycle of leaves—and genetic diversity. They are monitoring the timing of leaf out in the spring and senescence in the autumn to identify unique behaviors among individual sugar maples in Black Rock Forest in Cornwall, New York.

To analyze the genetic makeup of these trees, Seosamh collected leaf samples from dozens of sugar maples, stretching from Harvard Forest in Massachusetts to the Hudson Valley in New York, and all the way to Franklin, West Virginia. The DNA from these samples was carefully extracted and sequenced at the Pfizer Lab in partnership with the New York Botanical Garden. The data is currently being filtered and visualized using bioinformatics software, with results forthcoming. This work represents a crucial step in understanding the foundational population-scale genetic diversity of these iconic trees.

From the Lab to the Land: Bridging Theory and Practice

Despite his deep familiarity with the maple genome and his work on genetic differentiation among distinct sugar maple populations, Seosamh had never learned the practical side of maple sugaring—the “joys, difficulties, and deliciousness” that come from producing the liquid gold.

The FGU internship changed that completely.

Working directly with producers, Seosamh learned the essential hands-on skills of sustainable maple production. He saw how the simple process of tapping a tree and collecting sap connects livelihoods to the health of the forest. He learned about the different kinds of taps and collection methods and gained a new appreciation for the sheer amount of work required to transform sap into syrup.

This experience showed him a new paradigm of learning, one that values direct engagement with communities and the environment. It highlighted a holistic connection between human well-being and the health of the forest, demonstrating how a community that relies on its natural resources becomes a dedicated steward of them.

What He Learned: Beyond the Basics of Tapping

Tapping maples is not as simple as it sounds. Seosamh learned that producers immediately run into complexities like determining the optimal hole size to drill, what size spouts and tubes to use, and exactly when to tap.

Additionally, questions naturally come up later in the season, such as when to remove the taps, whether to clean the tubes, how to clean them, and whether to leave the tubing up year-round.

His journey with these questions started with a lot of reading, followed by conversations with staff at FGU and local producers. He learned quickly that tapping maples, like many things, is a process that continues to be refined.

For example, using 3/16” tubing instead of 5/16” tubing can save money and increase production through natural vacuum, but it also requires at least an annual sanitizing. He also learned that many evaporators used today are heated by wood. This was surprising to him, as someone who only uses wood for heat on camping trips. Some evaporators use gas, and there is even a new evaporator powered only by electricity. He was shocked to find out that an electric-powered evaporator is a new concept. He expected that it would be the standard at this point in the advancement of technology. It began to make more sense, though, when he considered the common location of sugarhouses.

They are usually not close to electric lines, which means that a non-grounded fuel source like wood or gas is more accessible for most maple producers. This is just one example of the challenges in maple production that he had never thought of before.

Tubing

In regard to the tubing, Seosamh learned that if he were just starting to tap maples, he would probably give the 3/16” tubing a shot. The savings on tubing, as well as the reduction in the amount of plastic used in a sugarbush, were really appealing to him and to plenty of maple producers looking for ways to improve their sugaring methods. Early and unpublished research from FGU shows that using 3/16” tubing in tandem with a mechanical pump can provide greater sap quantity than 5/16” tubing. Even without a mechanical pump, 3/16” tubing outperforms 5/16” tubing in sap yields. However, not using a mechanical pump with the 3/16” tubing does have some drawbacks, like increased backflow and the need for a 34’ elevation decline to achieve maximum pressure in the natural vacuum. While some people may be turned off of 3/16” tubing because of the necessary annual sanitizing, Seosamh thinks that it’s probably best to sanitize the lines anyway in order to retain as much sap as possible and reduce contamination and buildup over time, regardless of whether a 3/16” or 5/16” tubing system is used.

Tree Physiology

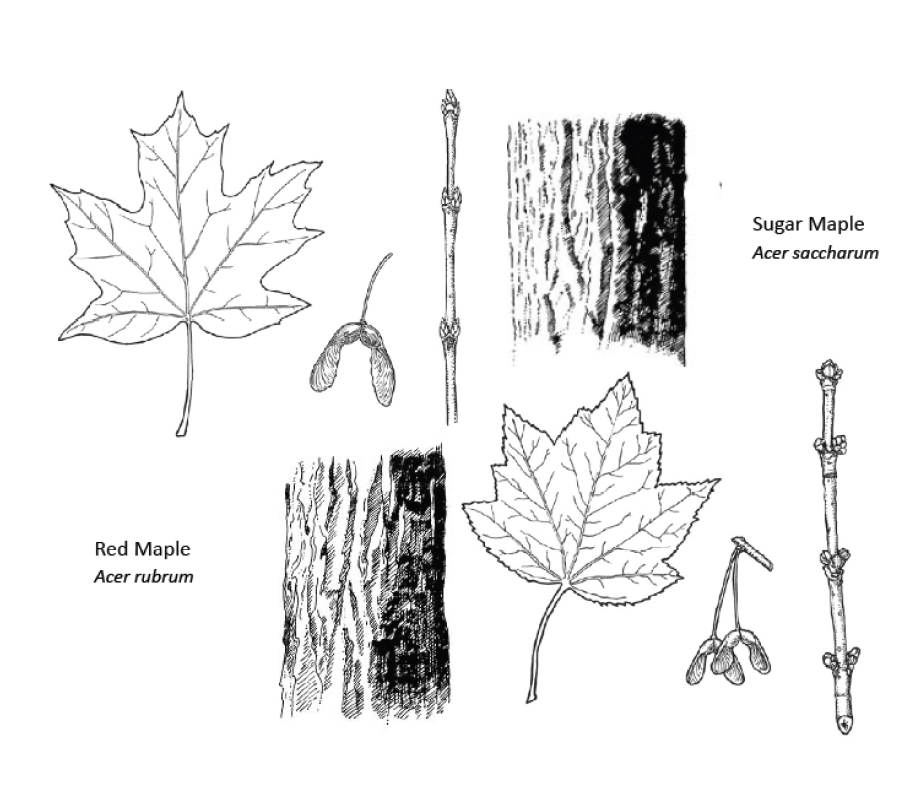

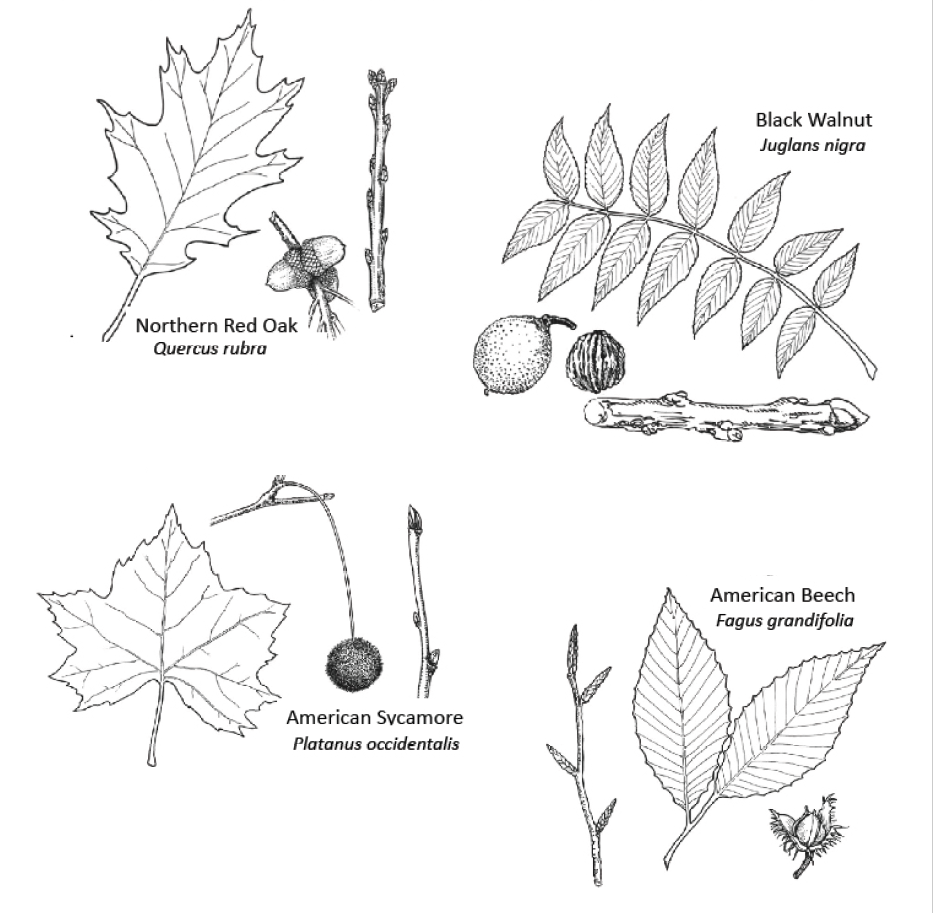

While he knew some tree physiology before interning with FGU, he learned quite a bit more about the physiology of maples, sycamores, and walnuts this summer.

The reason maples can produce so much sap is because they have a diffuse-porous hardwood which causes the sap to fluctuate within the tree in relation to the external temperatures.

Before his internship, he thought that maples were tapped in the autumn and early spring as the nutrients in the tree were returned from the leaves and branches to the roots for the winter and vice-versa. He had no idea that the sap moved based on pressure fluctuations induced by the freeze-thaw cycle in mid-to-late winter. Similarly, black walnut and American sycamore are semi-porous diffuse hardwoods, which means that a smaller amount of sap moves through the xylem during these pressure fluctuations. Alternatively, non-porous diffuse hardwoods like oaks do not move their sap through the xylem in the winter. Instead, it is all stored in the root system, so no matter how much you tap an oak in the winter, you simply will not get sap from it.

Alternative Syrups and Maple Products

Before this internship, Seosamh had no idea that syrups were actively being produced and sold from black walnut trees and American sycamores. Furthermore, he was astounded to see the incredibly high price for a gallon of black walnut syrup in comparison to maple syrup. Additionally, it is amazing that this can add another source of revenue for syrup producers with a plethora of black walnuts on their land by using the same equipment already used for maple syrup production. FGU is doing some amazing work with local landowners right now on refining the methods and equipment used for producing black walnut syrup. Seosamh thinks this is particularly interesting because it is such a niche product with a high demand that is simply not being met. If he were a landowner with a lot of black walnut trees, he would likely be on the phone today to talk about using his trees to further the body of knowledge around best practices for tapping black walnut and how he can start making money from those beautiful trees.

FGU is doing some amazing work with local landowners right now on refining the methods and equipment used for producing black walnut syrup.

Seosamh thinks this is particularly interesting because it is such a niche product with a high demand that is simply not being met.

If he were a landowner with a lot of black walnut trees, he would likely be on the phone today to talk about using his trees to further the body of knowledge around best practices for tapping black walnut and how he can start making money from those beautiful trees.

Seosamh thinks this is particularly interesting because it is such a niche product with a high demand that is simply not being met.

If he were a landowner with a lot of black walnut trees, he would likely be on the phone today to talk about using his trees to further the body of knowledge around best practices for tapping black walnut and how he can start making money from those beautiful trees.

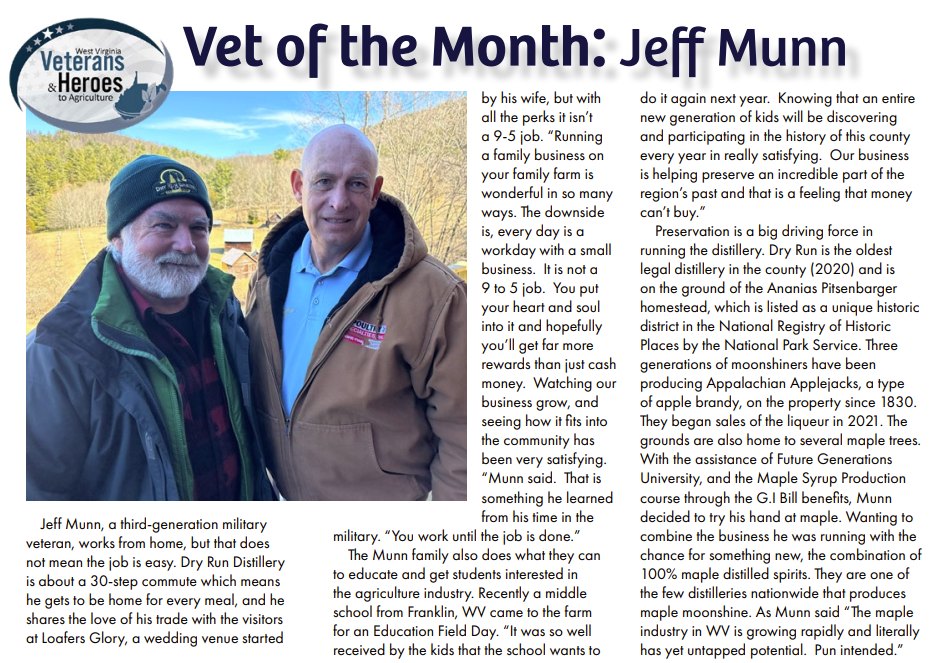

Seosamh knew Jeff Munn of Dry Run Spirits for years before this internship, so maple-based alcohols were not new to him. However, he never fully appreciated the creativity and craftsmanship that went into making his maple moonshine and maple liqueur. While Jeff is not the first person to do it, he is the first person Seosamh knows who produces maple-based alcohols, which makes him think of the potential for other creative maple products.

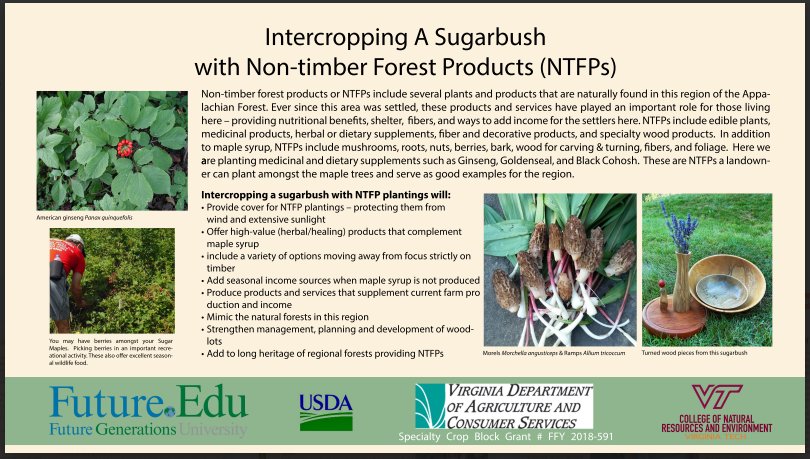

One of the great issues facing our planet today is climate change. Much of this is caused by releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which creates many unintended consequences. One thing that can help prevent severe climate change is sustainable agroforestry. In other words, how can landowners produce food products for themselves and even at a commercial level without deforesting their land?

Deforestation releases carbon from its stores in trees and soil as well as the many organisms that rely on the forests and releases it to the atmosphere. This is not good for the planet or for farmers in the long term. Many folks in the Franklin area (Seosamh included) are descended from the Irish, and a major reason why they live here and not in Ireland is because of crop failure that caused mass starvation and poverty. As it was then, it is still now: it is not good for farmers to rely on one product. Diversifying the products made on your land can protect farmers from financial devastation if disease or consumer behaviors force a product to be less lucrative than before.

Non-timber forest products are an opportunity for landowners to look at their forests in a holistic way as a sustainable method of food production and environmental stability. While maple, walnut, and sycamore products are wonderful, a forest has many layers and should be viewed in both a vertical and horizontal way. Some opportunities for diversification can include beekeeping, blueberries, blackberries, sunflowers, gooseberries, pawpaws, and plenty of others. Additionally, mushroom farming and consumption has been steadily increasing over the past 12 years while production levels have slightly decreased. This creates greater value for mushrooms, and a great opportunity for landowners looking to diversify and increase their income.

Among this diversity of NTFPs, the three biological kingdoms of animalia, plantae, and fungi are found. This is indicative of how viewing the forest holistically also allows a high level of biodiversity to thrive in the landscape, utilizing the interconnectedness and interdependency inherent in a forest to create sustainable sources of crops and revenue for rural areas.

A New Direction for Future Research

This experience has inspired Seosamh to consider a new direction for his future research. While his current work on genetic diversity doesn’t directly inform on-the-ground practices, his time at FGU has made him want to shift his focus toward more integrative research, perhaps for his Ph.D., that links scientific data with community-led solutions.

His vision is to move beyond simply analyzing genetic data in a lab. He now wants to explore how his findings can be applied to real-world challenges, such as how sustainable harvesting methods might influence the genetic resilience of a forest over time. By combining cutting-edge science with the traditional knowledge of producers and communities, he hopes to develop actionable strategies that will help preserve our forests for generations to come.

Seosamh’s journey from a city-based researcher to a hands-on agroforestry intern highlights a crucial point: the future of our forests depends on more than just data. It requires a synthesis of scientific inquiry, traditional wisdom, and active community engagement. His time with FGU provided a vital bridge between his academic knowledge and the practical, on-the-ground work that truly makes a difference.

By combining cutting-edge science with hands-on, community-based learning, Seosamh’s internship gave him a comprehensive understanding of what it takes to build resilient human and natural systems. His story shows that even a student from a place as urban as New York City can play a vital role in preserving our forests, one maple tree at a time.